During Prohibition (1915-24), too many people in Saskatchewan were drinking illegally, thanks to bootleggers. Prohibition had contributed to a marked increase in crime and violence. The new slogan became “moderation.” In 1924, the Saskatchewan government repealed Prohibition, established the provincial liquor board and implemented a new system of severe liquor control designed to limit alcohol consumption.

Highly restrictive liquor regulations did nothing to improve business at Saskatchewan’s long-suffering hotels. Under the Saskatchewan Liquor Act of 1924, hard liquor, beer and wine could only be purchased from government liquor stores. There were only two places that Saskatchewan people could legally drink: in their own home or in a hotel room in which they were registered. As a result, nightly drinking parties took place in hotels, to the great annoyance of owners and other guests. “While the liquor stores sell the desired drink and secure the profit, the onus is unpleasantly placed on the hotelmen of providing the room wherein the liquor may be consumed,” Wes Champ, president of the Saskatchewan Hotels Association (SHA) explained in 1925.

The SHA submitted a petition with 70,000 signatures to the provincial government in 1928 asking for legislation permitting beer parlours. The petition was denied. When the Depression hit in 1929, Saskatchewan’s hotels drifted into further debt and decline.

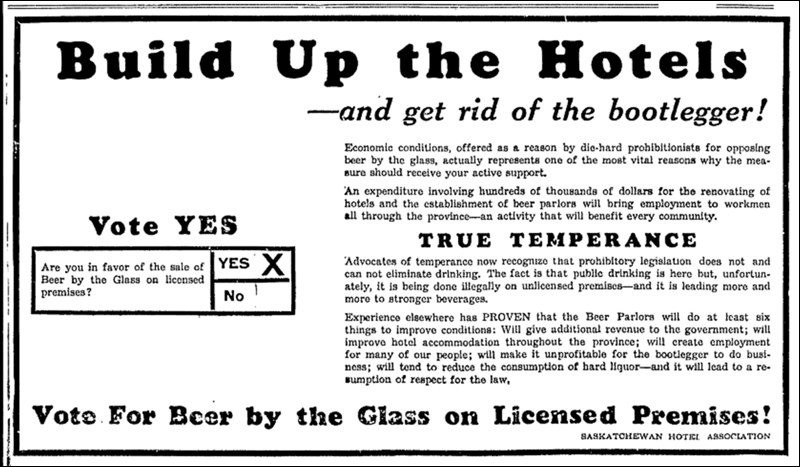

In 1934, a plebiscite was held during the provincial election that asked the question: “Are you in favour of the sale of beer by the glass in licensed premises?” The plebiscite carried by 30,130 votes. The final count was: “yes” - 191,722; “no” - 161,592. Half the majority was from Regina and Saskatoon; many rural areas voted against it.

On Jan. 22, 1935, after 20 long, dry years, the Saskatchewan government finally introduced the sale of beer by the glass, providing a welcome source of revenue and some relief for the hotel business. The rules for beer parlours seemed designed to make them as unattractive as possible. Customers could drink only while seated. There could be no sale of food, no dancing and no entertainment of any kind in beer parlours. Women were not allowed. The only thing they could sell in these cheerless places was beer.

By April, hundreds of Saskatchewan hotels were applying for liquor licences. Hotelkeepers had to spend money to fix up their beer parlours, but as they went further into debt, it was hoped that, with the anticipated revenue, they would be able to carry on.

The next big obstacle for the hotels was the question of “local option.” The new legislation allowed communities to vote on whether they wanted beer parlours in their hotels. In Carlyle, controversy raged for weeks over whether the Arlington Hotel should be allowed to apply for a beer parlour licence. In the end, 123 voted “yes and only seven voted “no.” “One old timer chuckled that he couldn’t find one solitary person who admitted to a ‘yes’ vote, so he could never figure out where the majority came from,” the Carlyle history book records. Some towns defeated the local option vote and their hotel owners had to wait three years before they could reapply for a licence.

Saskatchewan’s hotel industry did not fully recover from the blight of Prohibition and the ravages of the Depression until the return of better economic conditions during the Second World War.

*

Saskatchewan Hotel Association’s ad prior to the provincial plebiscite vote, Regina Leader-Post, June 16, 1934.

The Temperance campaign’s ad in the Regina Leader-Post, June 16, 1934.