WESTERN PRODUCER — Canada’s wild pig fighters are increasingly looking to the sky.

Drones, thermal cameras and AI-assisted image tagging are among the tools transforming how researchers and control programs are tackling Canada’s , attendees heard during the second Canadian Wild Pig Summit April 30.

Why it matters: Wild pigs are an on the Canadian Prairies. Conservation experts cite damage to local ecosystems, while farmers point to crop damage and .

Aerial technology has become a vital part of wild pig surveillance and control, said Travis McGee, a research technician with Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources. The ministry’s drone fleet currently includes three models from drone company DJI: the Mavic 3, the Matrice 30, and the newly acquired Matrice 350.

“Our Mavic 3 has great optical camera and thermal camera as an all-in-one package and is easily put into a backpack to use in remote applications, whereas our Matrice 30 and our matrices 350 are much larger. They come in really big cases and so they’re not easily brought into the field,” McGee said.

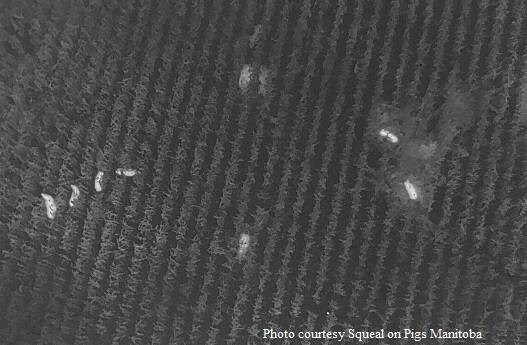

Aerial and thermal imaging shows wild pigs in a field of corn. Photo: Squeal on Pigs Wild pig control goes high-tech

The equipment provides 40 to 50 minutes of flying time and operates in a range of weather conditions, although smaller drones are less suited to wet or windy conditions, he added.

Everyone operating that equipment holds an advanced licence and flight missions are submitted and tracked using a platform called Fly Safe, listeners heard.

All three drones exceed Transport Canada’s 250-gram limit, over which there are more stringent rules for licensing and registration.

Watching wary pigs

The drones’ thermal and regular optical imaging cameras let the wildlife technicians find and watch animals without disturbing them, McGee said.

“We were doing some duck … counts last summer and we were able to spot a one-inch-by-one-inch solar transceiver on the back of a duck from 60 metres in the air.”

Thermal imaging, in particular, has been key for spotting wildlife at night or under cover.

Dense bush, though, can be a challenge at any type of day.

“Thick vegetation can reflect the infrared light in the daytime and block the animal target underneath, so you may not always see the animal because the forest canopy is not allowing you to see that heat signature on the ground,” he noted.

Operation success

McGee cited two southern Ontario wild pig removal operations where the drones were used extensively, in Pickering and Hawkesbury. The Pickering project resulted in the removal of 14 wild boar.

“These aircrafts were instrumental in confirming the number of animals that we were looking for and let us know when we actually had all the pigs in the trap to trip it,” he said.

In Hawkesbury, staff were working with challenging terrain. The cattails and wetlands that dominated the area made aerial support essential for both wild pig detection and safety co-ordination.

“Locating the animals in six-foot high, dense cattails was impossible without an eye in the sky,” McGee said. “The project could not have been completed without the drones.”

The ministry plans to explore additional applications, including animal monitoring, telemetry, mapping, baiting, and possibly darting.

Camera eyes on wild pigs

Another technology-driven project on the other side of the country is working to monitor wild boar near Elk Island National Park in Alberta.

The initiative, led by Hannah McKenzie, a wild boar specialist with Alberta Agriculture, tested how detection rates vary with camera height and also employed a scent lure.

“The Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI) has done a lot of work with remote cameras, and they use a camera height of one metre … However, the half metre is more commonly used for wild boar in camera studies in Europe,” McKenzie said.

The project also classified each site by land use and proximity to farms and park boundaries.

Game cameras help researchers and wild pig control projects observe and track the invasive species. Photo: Devin Fitzpatrick and Mathieu Pruvot Wild pig control goes high-tech

The project has yielded just a single detection so far (in November 2024), but researchers say it’s offered valuable insight into logistics, detection strategies and landowner relations.

That one detection yielded a 15-image sequence, McKenzie said, and also verified the value of the scent lure.

“We were able to see that the wild boar did check out the scent lure … and, in fact, the lure seemed quite popular with many species as well,” McKenzie said.

The lure used was a strawberry-scented Vaseline inside PVC tubes staked to the ground. A revised design will suspend the lure above the snow to improve scent dispersal.

“This was really valuable, because the trappers had an opportunity to make some connections in the community, and this really sets them up for success for future trapping efforts,” she said.

While data is still sparse, McKenzie is optimistic that detections will increase as wild boar shift their habitat use with the seasons.

“We believe that the wild boar spends the majority of their time in the park, but they do leave Elk Island to feed in the surrounding agricultural landscape … mainly in the late summer and fall, when the crops are mature,” she said.

She also suggested that the team might explore AI tools to speed up their image review process.

Verifying action plans

Another winter aerial survey in east-central Saskatchewan confirmed suspicions that wild pigs are clustering in wetland habitats and confirmed a hot spot near Tisdale.

“This was essentially an aerial reconnaissance for … east-central Saskatchewan, and also looking at components within the monitoring area to try to come up with a total count,” said Doug Schindler, president and senior scientist with Joro Consultants in Selkirk, Man.

The survey, conducted by helicopter in January 2025 under contract with the Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation, recorded 107 animals in one priority zone alone.

“We had one sounder … and there was a bunch of little piglets that came out. They were less than the size of a toaster,” Schindler said.

Wild boar are captured on trail cameras near Elk Island National Park, Alta. Photo: Devin Fitzpatrick and Mathieu Pruvot Wild boar are captured on trail cameras near Elk Island National Park, Alta. Photo: Devin Fitzpatrick and Mathieu Pruvot Wild pig control goes high-tech

Schindler said wild pigs favour dense cattail and willow swamps for both food and cover. “They forage for cattail roots like crazy,” he said.

The animals tend to be highly clustered in winter, not spread across the landscape.

The findings helped fine-tune trapper efforts and supported Saskatchewan’s current strategy. Aerial hunting could be the next step, Schindler said.

“We are qualified for that … we could have probably quite easily taken out a lot. You can get right down on the deck, and you can almost reach out and touch them.”

Schindler hopes to expand the winter survey program and suggested that high-resolution imagery could further improve habitat modeling and planning.

The summit was hosted by Animal Health Canada, Squeal on Pigs and the Manitoba Pork Council.

About the author

Miranda Leybourne was born in northeastern Ontario and raised in various gold mining towns across North America. She received a diploma in Media Studies at Assiniboine College in Brandon in 2007 and worked in radio and daily news before joining Glacier FarmMedia. Passionate about regenerative and local agriculture, Miranda loves spending time in the outdoors with her family. In her spare time, she’s an avid gamer and enjoys writing historical fiction.