WESTERN PRODUCER — Western Canadian farmland is cheap when compared to Europe and the United States, says the director of an investment fund with offices in Calgary and Toronto.

Cropland values may have tripled or quadrupled or quintupled in the last two decades on the Prairies, but the land is still undervalued when productivity is factored into the equation.

“A tonne of wheat growing capacity in Canada…. Is about C$2,500-C$3,000 per tonne,” said Stephen Johnston, director of , which owns about 140,000 acres of farmland in Western Canada.

In comparison to the Prairies, it costs about C$10,000 to acquire a tonne of hard red spring wheat production in France, Germany, the U.S. and other parts of the developed world, Johnston said.

“Canada is still quite deeply discounted, when you look at this very fundamental variable,” he said, adding the $3,000 per tonne for Canada and $10,000 for other countries are averages.

The actual figures would vary from region to region, within a country.

Johnston, who spoke to the Western Producer from his office in Calgary, said Omnigence has been investing in Canadian land for 17 years. It’s farmland fund, , owns land from northwestern Ontario to British Columbia, with a valuation of about $500 million.

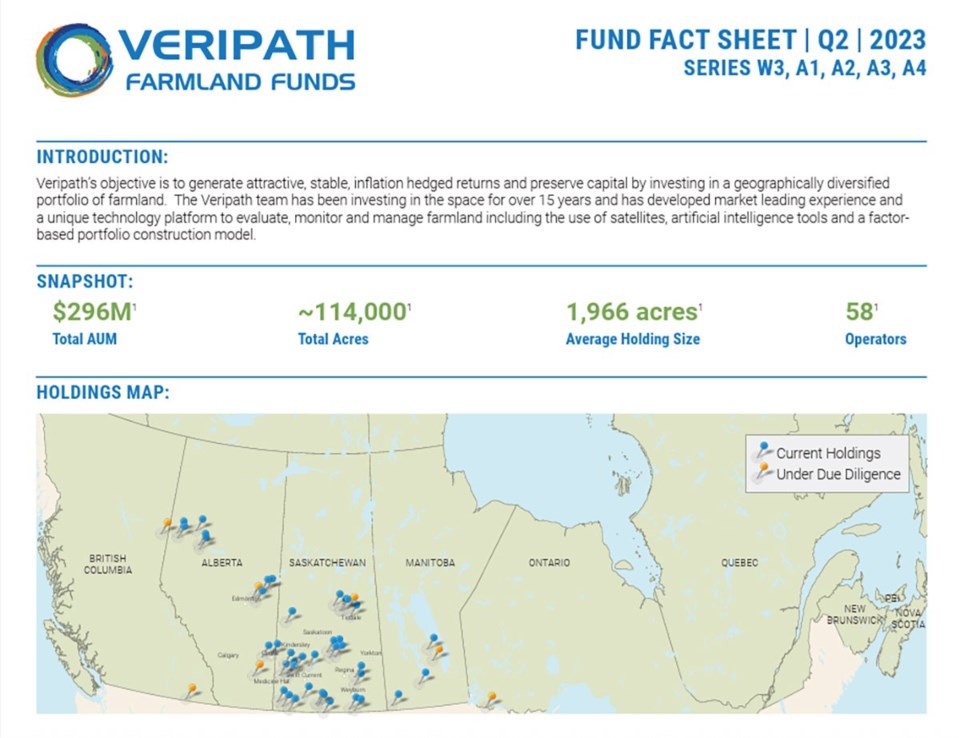

In 2023, Veripath Partners owned about 114,000 acres of agricultural land in Western Canada. The Calgary based investment fund now owns about 140,000 acres, valued at $500 million. | Screencap via Veripath Partners

In 2023, Veripath Partners owned about 114,000 acres of agricultural land in Western Canada. The Calgary based investment fund now owns about 140,000 acres, valued at $500 million. | Screencap via Veripath Partners

While some investors focus on the price per acre, Veripath is obsessed with the amount of crop that can be grown and what it costs to acquire that production.

“One of our core portfolio variables is we’re looking for the lowest price (per) tonne of productive capacity,” said Johnston, who has three decades of experience as a fund manager, according to the Omnigence website.

“We normalize for hard red spring wheat (production).”

The managers of Veripath also consider other factors when evaluating the value of farmland:

- Crop production trends (are yields increasing on the piece of land?)

- Production volatility (are yields stable, or do they yo-yo between extreme highs and lows?)

For the sake of an example, assume there’s a section of land near Tisdale, Sask., that has a history of wheat yields that have increased over time.

Over the last five years, production has been 60-70 bushels per acre — or 1.63 to 1.9 tonnes per acre.

If the value of that land is $4,000 per acre, the cost per tonne of production is $2,100 – $2,500 per acre.

So, a bargain, using Johnston’s math.

“Once you’ve normalized for the price of a tonne of (wheat) yield… you can compare land in Saskatchewan, to land in France…. To land in the panhandle of Texas,” he said.

“There is no developed market that’s anywhere near the pricing of Canada… it is very deeply discounted, even after all the appreciation we’ve had.”

Is prairie farmland still a bargain?

Johnston’s analysis is interesting, but the notion that Western Canadian cropland is cheap goes against conventional thinking.

Since about 2007, the price of farmland on the Prairies has skyrocketed — increasing 300 to 500 per cent — depending on the region of the Prairies.

Using data from FCC:

- In 2006, the average cropland value in northwest Saskatchewan was $446 per acre

- By 2024, the average price of cultivated land in the same region was $3,500 per acre

What’s driven up prices, though, is not investors like Johnston.

Crop production has been profitable for much of the last two decades and Prairie farmers are willing (and able) to pay market prices, or higher, to acquire more land.

“The investors don’t change farmland values,” said Ted Cawkwell, a real estate agent in Saskatoon who runs the Cawkwell Group and specializes in farmland transactions, in 2024.

“What affects farmland values is the profitability of the farmers…. It all boils down to profitability.”

Plus, investors only own 1.5 to two per cent of the agricultural land in Canada. Their influence is small compared to producers who compete to purchase available land in their local area.

Looking ahead, Johnston believes that investors will acquire a larger share of Canada’s agricultural land.

“It’s a very overlooked asset class… (but) it is changing. What will bring the change, is stagflation.”

A period of slow economic growth, combined with rising prices for goods and services and high unemployment, is stagflation.

Under those economic conditions, investors struggle to find assets that generate returns. But agricultural land has a history of gaining value during periods of stagflation like the 1970s.

“As the stagflation risk gets bigger and bigger, you’ll see a lot more institutional (investor) interest in Canadian farmland,” Johnston said.

“Our (farmland) fund is now $500 million and in two or three years, it will be $1 billion.”

About the author

Related Coverage