WESTERN PRODUCER — The last time I wrote about straight-line winds in thunderstormswas a couple of years ago, and in that article, I discussed how global temperatures once again broke record levels. Well, looking at the latest data, it shows that May 2025 was the second warmest on record. Looking back, this May was only the second month in the past 23 months that did not surpass the 1.5 C pre-industrial threshold, which means there are some signs of cooling of our overheated planet, but not much. Computer models are still showing that 2025 will come in as the second or third warmest year on record.

Now on to this week’s severe summer weather topic — straight line winds. While most of us know that tornadoes can produce the most powerful winds on Earth and they can be truly awe inspiring to see, not very many of us will actually experience one. What I can pretty much guarantee, is that if you live on the Prairies, you will experience a thunderstorm that produces very strong straight-line winds. Sometimes these winds can be so strong and devastating that their damage is attributed to a tornado, and the only way to determine whether or not the damage was caused by straight line winds, or a tornado, is to look at the pattern of damage that has occurred. With tornadoes, the damage will be more random, with trees and objects broken and thrown in different directions due to the swirling air. With straight line winds nearly all the damage is unidirectional, or rather, in one direction.

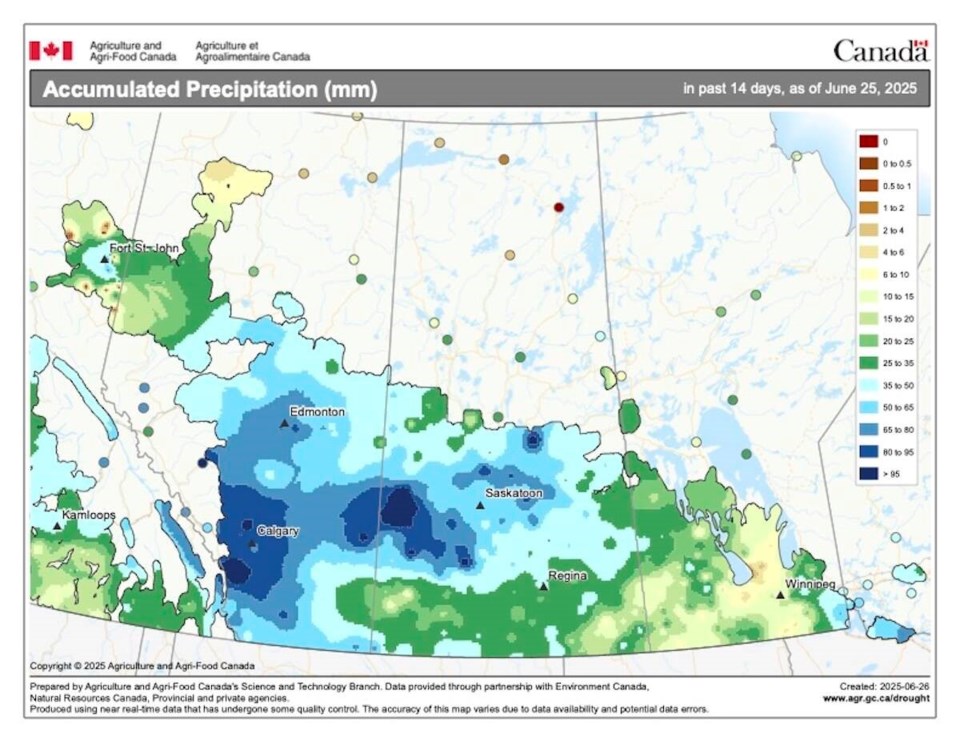

This map shows the total amount of precipitation that fell across the prairies over the 14 day period ending on June 25th. Looking at the map you can see that there was significant precipitation across most of southern and central Alberta along with central Saskatchewan.

Nearly all straight-line winds, or at least the really damaging ones, occur near the leading edge of a thunderstorm. Thunderstorms are made up of areas of updrafts and downdrafts. The updrafts are easy to understand, as they are the regions where air is moving upwards due to either being warmer than the air around them or by being forced upwards as horizontally moving air is deflected upwards by something like a cold front. Downdrafts are a little more difficult to understand, but only a little bit.

When a thunderstorm is moving in, we can often get that first big blast of wind that causes everyone to run for shelter and announces the arrival of the storm as the clouds open up and rain begins to pour down. There are two main causes of these winds. First, you have to imagine all the air that is rising up to the top of the storm has to go somewhere. In a strong storm, an overhead jet stream is trying to vent all this air away, but often not all of this accumulating air can get vented away. Eventually the amount of excess air that builds up becomes large and heavy enough, or the updraft weakens, and that air begins to fall back towards the ground.

Now combine this falling air with the rain that is also falling. As the rain falls from the storm, that rain is pushing on the air around it, much like when you spray something with a garden hose or if you have ever visited a big waterfall. This downward moving air hits the ground and then has to flow somewhere. The area of falling rain acts like a wall preventing much of this falling air from flowing back into the storm, so instead most of it is funnelled or pushed out in front of the storm.

These downbursts can be short lived, travelling and lasting only a short time. Or they can continue for long distances as the thunderstorm travels. These long-lived events are known as a derecho. While not that common in Canada, they do occur. Peak wind speeds in these downbursts can routinely hit over 100 kilometres per hour with some gusts peaking at over 200 km/h.

The worst derecho on record in Canada occurred in May 2022 in southern Ontario and Quebec. Winds speeds were recorded as high as 190 km/hr along a path that extended for nearly 1,000 km and took nearly nine hours to play out. Damages exceeded $750 million, making it the sixth-most costly Canadian weather disaster on record. Sadly, 12 people were killed, mostly from falling trees.

If you have lived through a few strong thunderstorms, you know that out in front of the thunderstorm is not the only place where strong straight-line winds can occur. Often, we can get very strong winds in the middle of the storm.

One of the reasons for these strong winds is the jet stream or strong upper-level winds. As you know, strong thunderstorms often need strong upper-level winds to help vent all the rising air. Occasionally, these strong winds can get caught up in a strong downdraft and they basically get deflected towards the surface. If they make it all the way down to the surface, they must spread out and can flow in several different directions depending on the angle that they came in from. This is why this type of straight-line wind can be confused with tornadoes, because these winds can often seem more chaotic than the winds that preceded the thunderstorm.

In the next issue, it is time once again to look back at last month’s weather. That’s right, another month will have come and gone, and we are now halfway through the year! As usual, we will also revisit the different long-range forecasts to see if anything has changed in the different outlooks.

About the author

Related Coverage